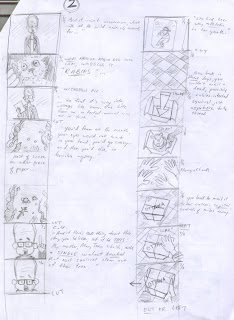

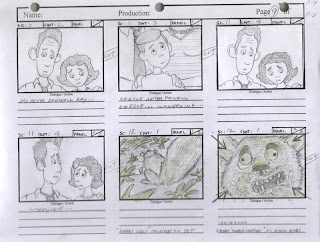

Click on pic to make it big, although not much bigger, sorry.

So now that I've beaten to death the process of the story development, the next stage I thought I'd explore is Puppets. As with story, everyone has his or her own process of development. This is mine.

Also, I'm writing this for a reader that is eager, generally talented, but not very experienced in stop mo production (in short, my students!) At points I discourage approaching puppet-making in certain ways. That's based on the assumption that you (faithful reader) are not already practiced at this medium, and that you do not have a workshop full of power tools and mould-making materials and chemicals.

From teaching stop mo for a few years now, I've really come to approach the medium from the pov of "what can the average but very passionate person achieve?" So I don't tend to promote methods that require special machines (although sometimes there's no way around using a jigsaw, for some set building stuff), tricky chemicals, foam ovens, mould fabrication, metal lathing, and so on.

So please bear that in mind as you read all these puppet-making entries...I am always trying to get talented and passionate people excellent results, as opposed to miring them in financial debt to buy expensive stuff, so they can achieve poor results cause they weren't focusing on the important fundamentals.

As I now step down off my soapbox, ahem...

I first look at the finished boards, to confirm what the puppet in question has to do, specifically. This is an extremely important aspect of design. As a very basic example, imagine a scene in which the puppet has to reach up and grab an apple from a tree branch. But you've designed (and built!) a puppet with very short stubby arms. When you come to shoot that "grabbing the apple" shot, guess what? Your puppet simply cannot do the action.

So if your character has to (for example) balance on tip toes, then leap into the air, hover for 5 seconds, then suddenly stretch its neck out like a giraffe, you've got a lot of serious design issues to consider. Conversely, if your character has to basically stand in one place, make some facial expressions, be capable of solid but not particularly complex animation, move his arms around, and basically LOOK good, that's a far more straightforward issue. And that's the case with the puppet above. He's the Dad puppet for my film.

In the interest of moving along, I'll just say this about designing and constructing puppets: it's as much mechanical design as it is artistic design. This holds true especially when you are designing AND making the puppet yourself. Puppets take a VERY long time to design and build, even simple ones. All the puppets in my film are fairly straightforward, and the story was in part designed to allow for that fairly simple puppet making. Again, when you are doing it mostly yourself (even with a massively talented and helpful assistant like I had), all aspects of the production are really intertwined as you move forward.

And when they start getting tricky (puppets, that is), having to do very particular actions, it gets very complex and very NOT possible for a do-it-yourself-er. But the specifics of complex puppet making is not only for another posting, its for an entire lifetime of practice and craft...

As you are designing a character, here are a few very basic things to consider. You'll notice most of them concern how to get the puppet to stay still while you are animating he/she/it!!

RIGS

Does the puppet have to have all its feet off the ground at any point? If so, that means you will somehow have to "rig" that puppet with a wire (that is secured to something out of camera) for those frames of animation. Later, you will have to digitally "clean up" those frames, removing the wire. Rig shots can be very simple (a ball landing in a glove), or very complex (10 witch puppets, all floating on broomsticks while juggling jack-o-lanterns). If a puppet needs a rig, it has to have that rigging point (where the wire will go) incorporated into the design.

BUTT MAGNETS

In my story, there's a scene with two puppets sitting on a park bench. How to get them to stay still while they are being animated? My solution was to design very strong magnets (called "rare-earth" magnets) into their butts! So when the sit down, I can put another magnet under the bench, and they will stay put. But I only knew to install these magnets cause I carefully consulted the finished boards. Always refer to your boards before designing.

TIE DOWNS VERSUS MAGNETS

Here's a good example of functionality versus design. If you design a character with lovely, tiny feet, she will look beautiful. But she will be very tricky to stand up. And standing up is the one thing your puppet REALLY needs to do well. If a puppet won't stand up securely, you are going to go bonkers trying to animate this wibbly-wobbly creature. Since this puppet in question has tiny feet, you'll need to use little nuts in her feet, that you can screw a bolt into from under your set. This is the "tie down" method of puppet making. An easier solution is embedding a rare-earth magnet in her feet. Now she will stand very easily, just by placing another magnet under your set. But now, since the magnets are big, she has clunky clown feet. Which is more important, that she is easy to move, or that she looks lovely?

COSTUMES

A complex area of puppet making, this. Is your character a human? If you look at the Dad puppet, he has long pants, and a short sleeved shirt. Pretty "normal" attire. The long pants are good, cause they cover a lot of skin. Under the pants can just be armature, and foam (for bulk). But the short sleeve shirt is tricky, cause it leaves exposed a lot of arm flesh. And since I was making the puppet parts from building up with liquid latex, getting a "smooth" look over all that area was going to be tricky. If he had long sleeves, that would be much easier. I'd only have to worry about smooth hands (as his arms would be under fabric). But the story was very much set in the summer, so he HAD to have short sleeves. So I HAD to pick up the challenge of geting smooth arms. See how costume hugely effects puppet making?!

Further, what if instead of a human Dad, he was a cat Dad? Imagine he still had these cloths, but was also covered in fur. What is that fur made from? How do you apply it to the puppet? Will it stay still during animation?

How about if instead of a cat Dad, he was a lizard Dad? Now you have smooth shiny scales to create. How do you do that?

There's no way I can really go into detail on this here! But suffice it to say (for now) that just cause you can imagine it, and draw it, DOESN'T mean you can build it. Sure, SOMEONE could build it (for you). There are hugely talented pros out there. But it will cost you quite possibly thousands. What can YOU make?

Personally, I can't even make the simple costume depicted! I know my weak areas, and constructing costumes is one of them. I can design, if it's simple, but I can't make. I PAY to get my costumes made. And they are beautiful, and done quickly, and function properly. It's worth it to me, to get nice puppets. So I always budget for costume fabrication. Simple as that.

PUPPET HEADS AND FACIAL ANIMATION

I'll write more on the topic of puppet heads specifically, later. But in short, as you design, think about what your puppet head and face has to do. Let's say you have a tiger, and you design a character that will have a moving jaw. And he has lots of lip sync. You've just designed yourself into hell. The basic shape of that head (assuming it's fairly realistic) is enough of a challenge. Then a hinged jaw is very complex to design and fabricate (assuming you are working very indie). And all that lip sync will mean the very delicate structure of that jaw will be maxed out by all the detailed animation. The wires in there will break, and be very hard to replace. I always steer students away from this structural design for mouths. Again, it's about mechanical realities JUST as much as it about designing a pretty character.

In the example of the Dad puppet above, you can see he has a very simply little mouth. His character only has minor changes in mouth shapes, and in mouth positions. So for him, I designed a head that would be sculpted and hard (and stand up to frame-by-frame abuse by my hands), and that had NO mouth. Just a smooth space where the mouth would go. Then I used clay that was the right colour to match the head, that I simply pressed gently on to head. It could be moved and replaced and animated. This method of "hard head, soft mouth" puppet making is nothing new, it's used all over. It's slick and fast and effective in terms of conveying what you want, in a fairly simply technical way. It's the method I point most students towards.

Again, search your boards, see specifically what your puppet has to do, and go from there. If the Dad had tonnes of lip sync, using soft clay mouths that I whip up on set would not be practical. Instead, I'd make a "mouth kit" of mouth shapes that would be hard, and that could be tacked on with a tiny bit of wax. But still, it's the same basic concept- a hard hard, with external mouth pieces that get applied frame by frame.

Not saying this is the only way. Just saying it's a slick way that works.

Whew. I have a very strong feeling these puppet making postings are going to be rather technical, as opposed to philosophical. It's hard to resist falling into a "how to" approach, because with stop mo, there really IS a lot of practical stuff to learn.

Of course, in all aspects of the creation of art, there's room for philosophical considerations. It's just that production needs tend to take over (ie, deadlines) and now that story is locked in, it's usually a case now of "get it done".